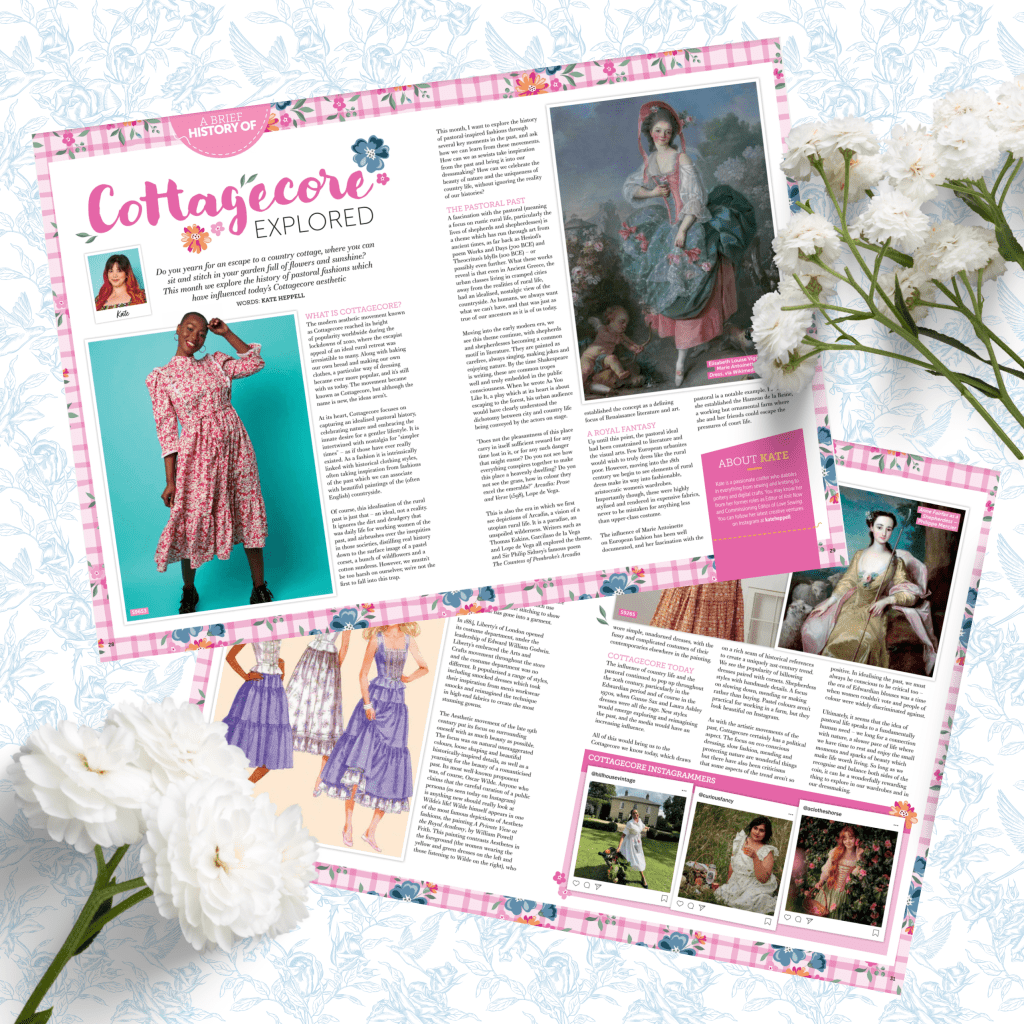

Do you yearn for an escape to a country cottage, where you can sit and stitch in your garden full of flowers and sunshine? This month we explore the history of pastoral fashions which have influenced today’s Cottagecore aesthetic!

This feature originally appeared in Love Sewing magazine issue 135.

What is Cottagecore?

The modern aesthetic movement known as Cottagecore reached its height of popularity worldwide during the lockdowns of 2020, where the escapist appeal of an ideal rural retreat was irresistible to many. Along with baking our own bread and making our own clothes, a particular way of dressing became ever more popular, and it’s still with us today. The movement became known as Cottagecore, but although the name is new, the ideas aren’t.

At its heart, Cottagecore focuses on capturing an idealised pastoral history, celebrating nature and embracing the desire for a more gentle lifestyle. It is intertwined with nostalgia for “simpler times” – as if those have ever really existed. As a fashion it is intrinsically linked with historical styles, taking inspiration from fashions of the past which we associate with beautiful paintings of the (often English) countryside.

Of course, this idealisation of the rural past is just that – an ideal, not a reality. It ignores the dirt and drudgery that was daily life for working women of the past, and airbrushes over the inequities in those societies, distilling real history down to the surface image of a pastel corset, a bunch of wildflowers and a cotton sundress. However, we mustn’t be too harsh on ourselves; we’re not the first to fall into this trap.

This month, I want to explore the history of pastoral-inspired fashions through several key moments in the past, and ask how we can learn from these movements. How can we as sewists take inspiration from the past and bring it into our dressmaking? How can we celebrate the beauty of nature and the uniqueness of country life, without ignoring the reality of our histories?

The Pastoral Past

A fascination with the pastoral (meaning a focus on rustic rural life, particularly the lives of shepherds and shepherdesses) is a theme which has run through art from ancient times, as far back as Hesiod’s poem Works and Days (700 BCE) and Theocritus’s Idylls (200 BCE) – possibly even further. What these works reveal is that even in Ancient Greece, the urban classes, living in cramped cities away from the realities of rural life, had an idealised, nostalgic view of the countryside. As humans, we always want what we can’t have, and that was just as true of our ancestors as it is of us today.

Moving into the early modern era, we see this theme continue, with shepherds and shepherdesses becoming a common motif in literature. They are painted as carefree, always singing, making jokes and enjoying nature. By the time Shakespeare is writing, these are common tropes, well and truly embedded in the public consciousness. When he wrote As You Like It, a play which at its heart is about escaping to the forest, his urban audience would have clearly understood the dichotomy between city and country life being conveyed by the actors on stage.

“Does not the pleasantness of this place carry in itself sufficient reward for any time lost in it, or for any such danger that might ensue? Do you not see how everything conspires together to make this place a heavenly dwelling? Do you not see the grass, how in colour they excel the emeralds?”

- Arcadia: Prose and Verse (1598), Lope de Vega

This is also the era in which we first see depictions of Arcadia, a vision of a utopian rural life. It is a paradise, an unspoiled wilderness. Writers such as Thomas Eakins, Garcilaso de la Vega and Lope de Vega all explored the theme, and Sir Philip Sidney’s famous poem The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia established the concept as a defining focus of Renaissance literature and art.

A Royal Fantasy

Up until this point, the pastoral ideal had been constrained to literature and the visual arts. Few European urbanites would wish to truly dress like the rural poor. However, moving into the 18th century we begin to see elements of rural dress make its way into fashionable, aristocratic women’s wardrobes. Importantly though, these were highly stylised and rendered in expensive fabrics, never to be mistaken for anything less than upper-class costume.

The influence of Marie Antoinette on European fashion has been well documented, and her fascination with the pastoral is a notable example. Famously she established the Hameau de la Reine, a working but ornamental farm where she and her friends could escape the pressures of court life.

Throughout her time as queen, she popularised two important styles of dress which were directly influenced by rural life. The first was the Robe a la Polonaise, inspired by Polish women’s national dress. This was a more relaxed style than French court dress, featuring swagged skirts, similar to those worn by shepherdesses and milkmaids. Perhaps the more daring and memorable fashion though was the Chemise à la Reine (literally translated as the Queen’s dress) – a loose and flowing dress which had more in common with underwear of the time than outerwear. Although its origins are contested, one popular theory suggests that the style originated with free women of colour living in the Caribbean. It was then adopted by local French women, as it was much more well-suited to the climate than the heavy layers that they had brought from home. The style then made its way back to France, where it was picked up and adapted by Marie Antoinette and her fashionable set.

The pastoral influence on fashion spread outwards from that point, with country styles being recreated in expensive materials, including bodices with no sleeves over very full chemises, exaggerated lacing and something of a contrived messiness in the way dresses were styled. Just as we see today, these dresses adapted and idealised the reality of working rural life. Sleeveless dresses were worn by shepherdesses who worked outdoors in the heat, but in high society they were recreated in delicate and decidedly impractical fabrics, clearly not to be mistaken for anything other than high fashion.

Artists and Aesthetes

When we move into the nineteenth century, there are two artistic movements in particular that it’s worth looking at when we’re thinking about the history of pastoral-inspired fashion and the ancestors of Cottagecore.

The first has its roots in the Preraphaelite art movement, where women were often portrayed in mediaeval-inspired costume, painted in natural hues. The Arts and Crafts movement took this ethos one step further, bringing the same ideals from the canvas into the real world. This movement’s focus was on preserving and honouring historic craftsmanship, with a strong emphasis on nostalgia and the satisfaction of work well done. Showing the handmade nature of items was a key theme in Arts and Crafts work, such as the hammer marks on copper and the chisel marks in woodwork. We see this influence in today’s Cottagecore styles which use slubby linen and visible stitching to show the work that has gone into a garment.

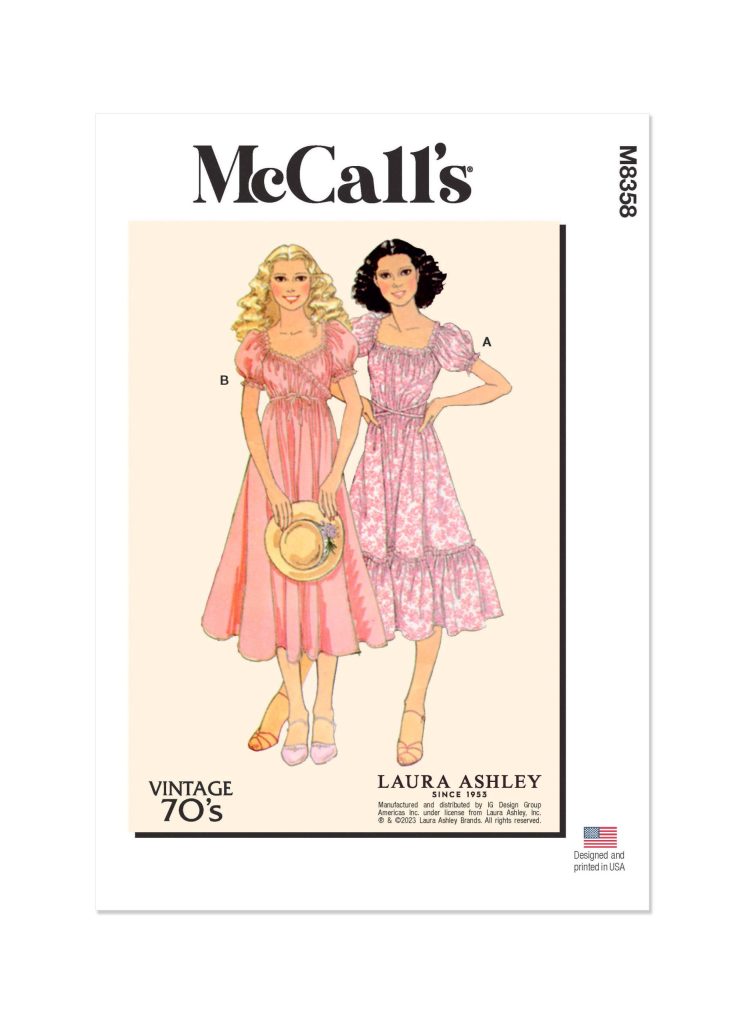

In 1884, Liberty’s of London opened its costume department, under the leadership of Edward William Godwin. Liberty’s embraced the Arts and Crafts movement throughout the store and the costume department was no different. It popularised a range of styles, including smocked dresses which took their inspiration from mens’ workwear smocks and reimagined the technique in high-end fabrics to create the most stunning gowns.

The Aesthetic movement of the late nineteenth century put its focus on surrounding oneself in as much beauty as possible. The focus was on natural unexaggerated colours, loose shaping and beautiful historically-inspired details, as well as a yearning for the beauty of a romanticised past. Its most well-known proponent was of course Oscar Wilde. Anyone who claims that the careful curation of a public persona (as seen today on Instagram) is anything new should really look at Wilde’s life! Wilde himself appears in one of the most famous depictions of Aesthete fashions, the painting A Private View at the Royal Academy, by William Powell Frith. This painting contrasts Aesthetes in the foreground (the women wearing the yellow and green dresses on the left and those listening to Wilde on the right), who wore simple, unadorned dresses, with the fussy and complicated costumes of their contemporaries elsewhere in the painting.

Cottagecore Today

The influence of country life and the pastoral continued to pop up throughout the twentieth century, particularly in the Edwardian period and of course in the 1970s, when Gunne Sax and Laura Ashley dresses were all the rage. New styles would emerge exploring and reimagining the past, and media would have an increasing influence.

All of this would bring us to the Cottagecore we know today, which draws on a rich seam of historical references to create a uniquely twenty-first century trend. We see the popularity of billowing dresses paired with corsets. Shepherdess styles with handmade details. A focus on slowing down, mending or making rather than buying. Pastel colours aren’t practical for working in a farm, but they look beautiful on Instagram.

As with the artistic movements of the past, Cottagecore certainly has a political aspect. The focus on eco-conscious dressing, slow fashion, mending and protecting nature are wonderful things but there have also been criticisms that some aspects of the trend aren’t so positive. In idealising the past, we must always be conscious to be critical too – the era of Edwardian blouses was a time when women couldn’t vote and people of colour were widely discriminated against.

Ultimately, it seems that the idea of pastoral life speaks to a fundamentally human need – we long for a connection with nature, a slower pace of life where we have time to rest and enjoy the small moments and sparks of beauty which make life worth living. So long as we recognise and balance both sides of the coin, it can be a wonderfully rewarding thing to explore in our wardrobes and in our dressmaking.